An introduction to private equity and private equity fund formation

What is private equity or "PE"?

The term "private equity" (PE) is frequently misunderstood, and following the global financial crisis, the misunderstandings associated with this term have become further exaggerated. The private equity (and hedge fund) industry has been used as a scapegoat for the crisis as a whole, being described as a destabilising market force and earning the unflattering nickname of "Vulture Capital" from its critics. But what really is private equity? This article seeks to introduce the reader to the main features of this business sector and outline some of the anticipated developments which will affect it in the future.

Private equity transactions cover a wide variety of activities that have one common feature: the source of the money that is funding the transaction. This source is usually a pool of (principally third-party) capital (the "fund") established in order to make investments and usually with a specific industry or geographic focus. Often the sectors targeted by private equity funds are unquoted securities rather than publicly quoted securities or government bonds (although sometimes exceptions can be made). Funds may conduct buyouts of public companies that result in a delisting of such public companies, so called "public to private" transactions. The majority of private equity investment originates from institutional and accredited investors who can commit large sums of money for long periods of time, as private equity investments may be held for long periods of time to allow, for instance, a turnaround of a distressed company or drive efficiencies. The fund is managed for the benefit of the owners of the fund's capital by a third party (the "fund manager") with a view to maximising value on disposal or exit and/or to extract attractive dividend yields and other returns on an ongoing basis.

There are a number of different types of investment focus (in terms of asset classes targeted) within the PE industry, although most funds choose to pursue their investment focus using just one or two strategies. Common PE investment strategies include:

- Venture capital: This is where the fund will provide necessary expertise and capital to a start-up, which may have been denied other sources of capital or may specifically be targeting the know how that a venture capital manager can contribute, in exchange for equity in that company.

- Growth capital: This refers to equity investments, most often minority investments, in more mature companies that are looking for capital to expand or restructure operations, enter new markets or finance a major acquisition without triggering a change of control of the business.

- Leveraged buyouts (LBOs): This involves using investors' capital to make a small down payment for the acquisition of a company and using leverage (i.e. third party debt) to finance the remainder of the acquisition cost, with the target's assets used as security. This type of investment strategy is no longer as prevalent as it was prior to the global financial crisis, when it was easier to borrow money to fund such transactions.

- Distressed debt/corporate restructuring: Distressed debt funds will buy corporate bonds (at very low prices) of companies who have, or are on the verge of, filing for bankruptcy. The fund will then either liquidate the company and take advantage of its preferential status to be repaid before other equity holders. Alternatively, where there is potential for the company to recover, the fund will reorganise the company and replace its management in order to return it to profitability. In such a situation, the fund will forgive the company's debt obligations in return for an equity stake in the company.

What is the current state of the private equity market?

In common with other business sectors, the private equity industry was hit hard by the financial crisis. Fund managers are, as a result, having to work much harder to get investors to commit capital. Fundraising during 2009 was particularly difficult with global fundraising totals down 65% on those in 2008 (Source: PE Online "Advancing to final close" 1/4/10). Many fund managers are finding that investors are being far more selective in their choice of fund manager, and are being more aggressive in the terms that they are negotiating before investing. An increase in consolidation between fund managers is expected, as is a period of many institutional investors either suspending or deferring their investment programmes.

Deal flow remains inconsistent and debt difficult to obtain, which is putting pressure on those funds with "dry powder" (i.e. funds to invest) to generate returns for their investors, although those funds that have access to capital are experiencing less competition when pursuing target assets. Exits continue to be difficult to complete, with capital markets offering limited windows of opportunity that often shut again all too quickly.

Lastly, the very large investors who were previously prepared to have their money managed by fund managers are increasingly exploring new forms of investment structures such as managed accounts, pledge funds, deal by deal funds, part-ownership structures of GPs and direct investments into portfolio companies, in an effort to increase their own financial returns.

As well as these business challenges, the private equity industry is also having to face an increase in regulation and calls for greater accountability. Proposed regulatory and tax reforms both in the US and in the European Union that aim to ensure that the industry does not pose a systemic risk to global financial markets will increase the regulatory burden on fund managers, require them to be more open in the way they do business, increase their compliance costs and force them to look at new ways to structure funds and the way that they receive returns in a tax-efficient manner.

What are the main benefits of setting up a private equity fund?

Despite the challenges that the private equity industry has faced recently, there are still very many attractive and compelling benefits to setting up, or investing through, a private equity fund.

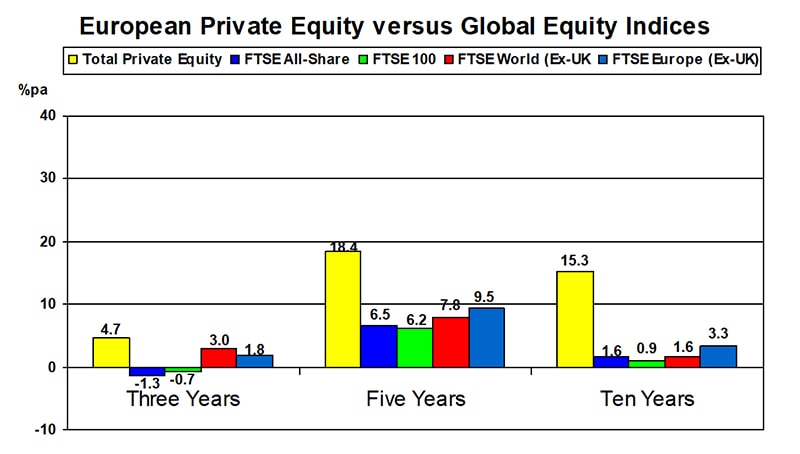

Perhaps the most important benefit is the opportunity that such pooled capital resources represent, especially in a world where bank lending is severely curtailed and valuations of businesses have dropped sharply. In many real senses, private equity may in the following years provide some exceptional returns to the savvy investor. You can see by the graph below that private equity is very attractive from a medium to long-term perspective and despite the recent financial downturn, continues to outperform other asset classes.

(Source: BVCA Private Equity and Venture Capital Performance Measurement Survey 2009).

The second benefit relates to tax. While many misunderstand private equity as being a method of "tax evasion", private equity funds are in fact normally created with corporate vehicles which are "tax transparent" or "tax exempt". This means that investors will be in the same tax position as if they were to make the investments into the underlying assets directly, and so rather than evading tax, investors are simply benefiting from tax efficiency and minimising their risk of paying "double tax". Historically the vehicles most suited to being used as private equity funds are limited partnerships, which are generally tax transparent in most jurisdictions, and companies established in off-shore jurisdictions which are effectively tax exempt in those jurisdictions.

Thirdly, private equity offers a relatively stable ownership structure. Private equity investments, because they usually follow a five to seven year "investment to exit" cycle, provide excellent opportunities to build a long-term relationship with an investee company, exercise real control and influence over the development of that company's strategy and, through the provision of advice and support for the portfolio company management team, to see the business improvement and growth. Private equity investments therefore act in quite the contrary manner to how they are sometimes perceived, as destabilising and short-termist.

Private equity also provides an alternative to debt finance, the effects of which were experienced by businesses in Kazakhstan who borrowed heavily and as a result were amongst the first businesses in the CIS to feel the consequences of the financial crisis and its liquidity constraints. In a private equity context, the investor shares the risk with the investee company whereas in the traditional debt context, the lender usually passes most of the risk to the borrower(s) and its guarantor(s).

Although the PE industry is faces an increased regulatory burden, traditionally, PE funds have been structured in such a way that they avoid much of the burdensome and costly regulation of traded companies, and it appears that despite the increase in regulation, this will continue to be the case. For example, PE firms have much more limited disclosure requirements than most companies who are required to spend significant amounts on public market disclosures relating to, for example, financial information and material transactions. Similarly, the traditional cost of regulatory compliance for the PE industry has been only a fraction of that of companies subject to public market regulation.

Who are the main players?

There are many well known private equity firms, both in the U.S. (including The Carlyle Group, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, The Blackstone Group, and TPG Capital) and in Europe (Apax Partners, Permira, 3i, CVC Capital Partners, Terra Firma, Candover, BC Partners). Please see the table below which lists the ten largest private equity firms in the world as of 2010 (Source: Private Equity International magazine's 2010 "PEI 300" rankings).

|

Rank |

Name of Firm |

Headquarters |

Capital Raised Over Last Five Years ($million) |

| 1. |

Goldman Sachs Principal Investment Area |

New York |

$54,584.0 |

| 2. |

The Carlyle Group |

Washington DC |

$48,175. |

| 3. |

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts |

New York |

$47,031.04 |

| 4. |

TPG |

Fort Worth (Texas) |

$45,052.05 |

| 5. |

Apollo Global Mgmt |

New York |

$34,710. |

| 6. |

CVC Capital Partners |

London |

$34,175.4 |

| 7. |

The Blackstone Group |

New York |

$31,139.4 |

| 8. |

Bain Capital |

Boston |

$29,239.6 |

| 9. |

Warburg Pincus |

New York |

$23,000.010 |

| 10. |

Apax Partners |

London |

$21,728.1 |

raised oVER

last five years

Rank Name of firm Headquarters ($m)

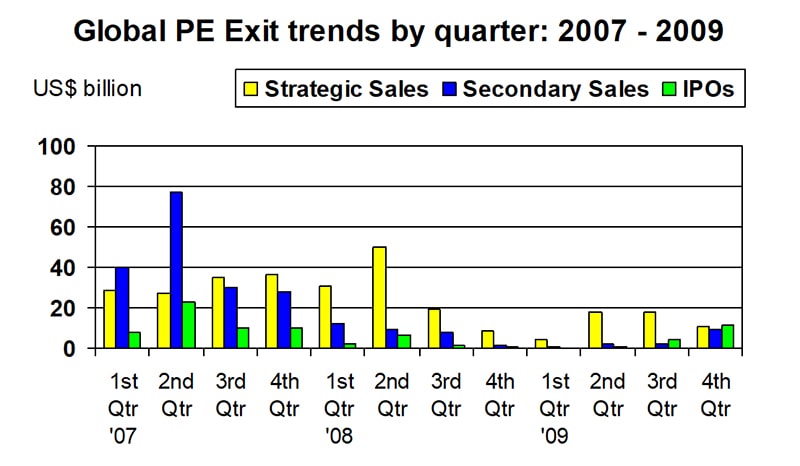

These firms have a huge influence and either control, or have at some point controlled, many of the major household brand names in the U.S. and in Europe and are in a great measure responsible for the success of these brand names. In 2009, PE firms raised $16 billion through the IPOs of 53 new companies, a slight increase from $11 billion through 52 transactions in 2008 (2010: global private equity watch of Ernst & Young (Pg 2, April 2010). Please see the table below which sets out the trends for global private equity exits, since the first quarter of 2007, differentiating between exits sought by strategic sales, secondary sales and IPOs (Source: 2010: global private equity watch of Ernst & Young).

According to a recent study by Preqin, UK private equity has provided an average five-year return of 17.5 per cent, beating all public indices examined in their study. In 2009 the average exit was valued at $321 million while the average acquisition cost totalled $100 million. (2010: global private equity watch of Ernst & Young (Pg 11, April 2010).These figures give an indication of the attraction of private equity over other investment classes.

The Kazakh private equity experience started in the mid-nineties when the EBRD established its first private equity fund in Kazakhstan. Since then there have been a handful of firms operating in the country. However, the domestic industry received a boost in 2007 when the Government established a number of investment institutions, including a fund of funds, thereby signalling their support for the industry.

What is the classic private equity fund structure?

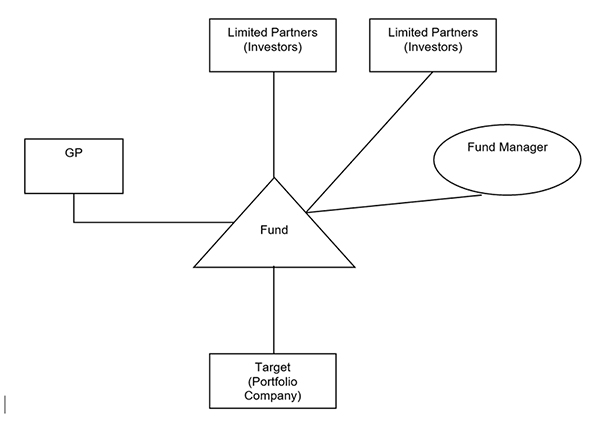

Private equity funds are most commonly structured as limited partnerships, and are "closed-ended" in nature (i.e. they have a fixed number of investment interests which are offered during an initial subscription period). Although the exact structure and characteristics of a limited partnership will depend on the jurisdiction in which the partnership is established, very broadly, each limited partnership will need to have at least one general partner (GP) and at least one limited partner (LP) (this is similar to a Kazakh "commandite partnership" where the general partner plays the role of a full partner). The GP will be responsible for the management of the fund and assume all of its liabilities. The LPs will be the investors in the private equity fund. An LP's liability to the partnership and its creditors is generally limited to the amount of capital that it agrees to contribute to the partnership. LPs will be restricted from taking part in the management of the partnership's business in order to protect their limited liability status, although in some jurisdictions there are safe harbours for matters in which LPs can be involved without them losing that limited liability protection.

Often the GP will delegate responsibility for the management of the fund to another entity called the fund manager. The fund manager will normally be a related party of the GP and will earn a fee, typically consisting of a share of the profits generated by the fund alongside a management fee calculated by reference to the size of the fund, for performing investment management functions on behalf of the fund. There may also be another affiliated entity to which responsibility is delegated, called the investment advisor, which will also receive a fee under the terms of an investment advisory agreement entered into between the fund manager and its investment advisor. Both the fund manager and any investment advisor will be structured so as to shield each of them from the GP's unlimited liability and, as they house the "intellectual capital" of the structure, GPs must be careful not to extend the role of any onshore fund manager and investment advisor beyond advisory work so as to avoid the fund becoming subject to tax in the onshore (high tax) jurisdictions. Please see the diagram below for a simple private equity fund structure, where the fund is a limited partnership.

Generally, investors in a private equity fund will commit to invest a certain amount of capital when the fund is established. As suitable investments for the fund are identified, these investors will be required to advance the capital they have committed to invest. This capital will normally be invested in companies which the manager has identified and which investment the GP has approved, commonly known as “portfolio companies”.

Although it varies from fund to fund, the typical lifetime of a fund, is around eight to ten years. This is normally set out as being (i) an initial four to five year "investment period" during which the fund identifies target assets and invests into them; (ii) a two to three year holding period during which the fund holds the assets, and (iii) a two year period when the fund seeks to sell its assets for a profit. There is commonly a provision allowing the GP to extend the life of the fund for up to two further years if necessary to allow the fund to be wound up in an orderly fashion, and a provision that provides that a fund manager may "overlap" and raise a new fund after a certain percentage of its current fund is fully invested.

As the private equity industry has historically been self-regulating, and has used existing forms of corporate and non-corporate structures, there has been little in the way of PE-specific statutes or legal codes to regulate the industry. Instead the relationships between the parties in the fund, such as the investors, GP, manager and advisor, have been governed by contractual arrangements, mainly through the limited partnership agreement (between the GP and LPs) and management and advisory agreements (between the GP and the manager and any advisors). An LP with a substantial investment may acquire additional rights, or require the GP to provide greater disclosure, by entering into a side letter, which supplements the fund’s offering, constitutional and subscription documents with respect to that LP by way of a bilateral agreement. These contractual rights can supplement or limit the general fiduciary duties that are owed by the general partner or investment manager, such as those duties that prevent a fiduciary from placing itself in a position where its interests conflict with those of its clients (i.e. the investors), and the duty of confidentiality, whereby a fiduciary must only use its customer's confidential information for the benefit of that customer.

If there are investments in jurisdictions which impose a withholding tax on income remittances, and there is no available double tax treaty, or the double tax treaty does not apply because of either the tax-exempt nature of any investors or the transparent nature of the partnership, there can sometimes be difficulties for the investors reclaiming the paid tax. However, this withholding tax issue can usually be addressed by making the relevant investment through a specially formed SPV, e.g. a Luxembourg conduit or Dutch BV, or by ensuring that the relevant investors participate through a special purpose "feeder" entity. Often investors from different jurisdictions will have different preferences for the kind of structure in which they would like to invest. In many cases this will lead to a number of multiple vehicles being established, each to achieve a particular structuring goal. The overall use of these master-feeder fund structures allows investors with very different tax, regulatory and governance restraints to all participate in one investment strategy.

Jurisdictions

The most common jurisdictions which are used to set up private equity fund vehicles are: Guernsey; Jersey; UK; Cayman Islands; Bermuda; British Virgin Islands; Ireland; Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Traditionally these offshore centres emerged as favoured locations due to their tax neutral environments, lighter touch regulatory regimes and the greater privacy they afforded private equity funds. While many of these jurisdictions are geographically small, they are important financial hubs which attract large amounts of capital. As at 31 December 2008 the Net Asset Value (“NAV”) of funds under administration (including both private equity and hedge funds) in the Cayman Islands was US$1.693 trillion.

The G20 summit on tax havens in April 2009 acted to “name and shame” several jurisdictions for their lack of tax transparency and cooperation, and this coincided with the release of a tax haven “black list” by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development ("OECD"). This list split out jurisdictions into separate sub-sections, defining some jurisdictions as on the OECD's "white" list, some on the "grey" list, and some on the "black" list. The OECD black list is the list of those jurisdictions which the OECD considers to be "tax havens", the grey list contains those "tax haven" jurisdictions who have agreed to implement the OECD endorsed transparency standards, but have yet to fully enact them, and the white list contains those jurisdictions which have in fact implemented the OECD endorsed transparency standards and are therefore not considered to be tax havens. In order to be promoted to the OECD's "white list" of jurisdictions compliant with international tax transparency standards, a jurisdiction must sign twelve bilateral Tax Information Exchange Agreements ("TIEAs"). TIEAs are agreements which are signed between two countries, establishing an official system whereby each country can request the financial and tax information regarding the citizens and corporations in the another country. This "information exchange" is does not directly prevent tax abuse, but is an aid to tax transparency. It should be noted that despite the promotion of numerous offshore jurisdictions, for example the Cayman Islands, from the "black list" to the "white list", there is still a stigma attached to those promoted jurisdictions, especially from the perspective of large European and US institutional investors. It is these large institutional investors in particular who are restricted by their internal governance codes in investing in some offshore jurisdictions due to the traditional reputation of such jurisdictions as "tax evasion havens".

The current “black list” approved by the Agency of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Regulation and Supervision of Financial Market and Financial Organizations (“FMSA”) consists of 43 countries including popular private equity industry locations such as; Cayman Islands, Guernsey (Channel Islands) and Mauritius, It should be noted that all of these jurisdictions have been on the OECD white list since 2 April 2009.

Who are the investors in private equity and what do they look for?

Investors into private equity are principally institutional investors (including pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance companies) and family offices acting on behalf of high net worth individuals. Potential investors will look at historical performance of previous funds operated by the same PE firm and will often view these as a projection of the possible returns of the new fund (although such performance is in no way guaranteed). For this reason, first-time funds will often find it much more difficult to raise funds than a firm which already has successful closed funds to its name.

Typically, investors will invest into a fund on the basis of the reputation of certain key individuals. As set out above, the experience and "intellectual capital" of such individuals will generally be housed in either the GP, the fund manager or investment advisor and the names of these key individuals will be crucial to an investor's decision to invest in a particular fund given their key role in identifying investments and implementing the investment strategy. Investors will therefore want to ensure that those key individuals continue to be involved in the management of the fund throughout the fund's investment cycle. "Key man" provisions are often included in the fund documentation, which provide the investors with certain specified rights in the event that a key individual leaves the employment, or stops devoting a certain percentage of his or her time to the activities of the fund. Such rights may include the suspension of the investment period, the reduction in the management fee awarded to the investment manager, or even the dissolution of the fund.

In the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis there was a considerable increase in the use of simplified fund structures for so-called "captive funds" and "club deals". The funds are used where for example a management team wishes to start its first fund on a limited budget by managing so-called “friends and family” money, accordingly the fund managers will not need to conduct a full marketing campaign and prepare an information memorandum, as they will have the investors already lined up. These structures are also used where an investor, such as a family office, holds a number of assets and wishes to “syndicate” those investments by dropping them into a fund structure, in effect as a form of capital contribution, and then offering further interests in that fund to investors for cash. This allows the existing investor to take some cash out of the fund and realise an immediate capital return. The clear advantage of these "captive funds" and "club deal" type structures is the cost, both in the establishment of the fund and in relation to ongoing costs. These structures will use simplified constitutional documents for the fund itself, and will most likely have fewer complicated contractual arrangements in relation to the returns that the manager receives.

The terms of the fund as laid out in the limited partnership agreement will be a crucial consideration for investors into any fund, and they will often be heavily negotiated. As will be seen below, there has been a shift in negotiation power in favour of the LPs, and they are using their increased bargaining power to negotiate key terms in their favour. During the negotiation of these terms, as well as changes to the commercial terms of the fund, an investor may also wish to explore possible structural changes that can be made to accommodate individual investor needs, e.g. parallel funds, alternative investment vehicles, and feeder funds.

Given the recent shift of power towards limited partners, the following terms of the LPA will likely be negotiated during fundraising:

- The level of management and performance fees. Investors are requesting both a reduction in the management fee (to nearer 1.5%) and a share in the performance fee, or a tiered performance fee that steps up once certain performance thresholds have been met.

- Key man clauses. As set out above, key-man clauses give investors some contractual protection in that should key persons depart, they can suspend the fund's ability to make investments (and the manager's right to management fee).

- Fund manager removal provisions. Historically, these provisions have been invoked rarely, but the lower returns being achieved by fund managers have caused investors to look more critically at whether they are happy with fund performance, and there have been a number of high-profile examples where investors have used their contractual powers to remove underperforming managers, suspend managers' ability to make investments or even to wind the fund up.

- Investment restrictions. Investors are increasingly focusing on ensuring that fund managers invest in a manner consistent with the investment strategy described in the fund's constitutional and marketing documentation and are requiring these clauses to be very clear as to the amount of capital that may be called annually, the size of individual portfolio investments, the geographic or industry focus, and the ability to invest into debt instruments, publicly traded securities and pooled investment vehicles.

The Institutional Limited Partners Association's Private Equity Principles (published September 2009, the "ILPA Principles") focuses on enhancing partnership governance, strengthening alignment of interests and improving investor reporting and transparency for the private equity industry. The buyout "boom" years altered the alignment between GPs and LPs that had previously served as a bedrock for the industry.

The ILPA Principles set out best practice and terms to be included in fund documentation including:

- Terms on payments and fees such as carry/waterfall, management fees and expenses. It is argued that clawbacks in particular should be strengthened so that when required they are fully and efficiently repaid. Also, management fees should not be excessive, covering only the normal operating costs of the firm. GPs should use other fees such as monitoring and transaction fees for the benefit of the fund, for example to offset management fees and partnership expenses throughout the life of the fund. It is also suggested that a high percentage of any GP's interest should be paid in cash rather than contributed through the waiver of the management fee. Furthermore, GP fees should be used to cover expenses relevant to the fund such as staffing costs and GPs should absorb any tax changes rather than passing them on to LPs.

- Strengthened governance provisions. Strengthening GPs' fiduciary duties and expanding the role of the Advisory Committee (the committee normally established to represent the views of a fund's investors and sometimes granted discrete powers to approve or reject the fund's administration) is strongly urged by the guidelines. They argue against exclusion of fiduciary duties. Greater transparency is also a feature with disclosures of financial information and information related to the GP all being suggested. Fund terms should also require the GP to present all conflicts of interest of which it is aware to the established Advisory Committee for review and seek prior written approval of any material conflicts and/or non-arms' length transactions.

Adoption of the ILPA Principles is voluntary, although proponents argue that it will serve both GPs and LPs to share objectives and have a better understanding of how a partnership can prosper. Prospective LPs will use the principles as a reference point in negotiations, but ultimately incorporation into each fund will depend on the bargaining powers of the parties.

In line with the themes above, the British Venture Capital Association recently announced the formation of the LP Advisory Board, a body charged with enhancing relationships and levels of understanding between GPs and LPs in the private equity and venture capital industry and which looks to identify common interests in LP community. Similarly, the EVCA LP Platform has recently announced that it will produce its own ILPA-style LP-focused best practice guidance. It is claimed that such guidance will be more "middle of the road", i.e. less slanted towards the interests of investors, than the ILPA principles.

Both the current and the previous United Nations Secretary-General have highlighted the potential for private equity to be effective tool of development on a world scale. However, there is a growing understanding that environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) issues can affect the performance of investment portfolios and appropriate consideration must be given to these issues. In April 2006, the 'Principles for Responsible Investment' ,a set of global best-practices for responsible investment, were launched by a partnership of; investors, the UNEP Finance Initiative and the UN Global Compact. They have been endorsed by increasing numbers of global institutional investors –representing more than eight trillion dollars in the first year alone – there are currently 760 companies and organizations signed up to these principles. The Principles provide for signatories to pledge the following:

- To incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes;

- To be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices;

- To seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest;

- To promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry;

- To work together to enhance their effectiveness in implementing the Principles;

- To each report on their activities and progress towards implementing the Principles.

Legal Issues

There are many legal issues which arise during the formation of a private equity fund, although these can very broadly be split into the four main phases of the fund's formation:

Pre-marketing

Prior to doing a road show fund managers will usually “test the water” and arrange informal meetings with potential investors in order to know how to best structure their offers so that they will be of most attractive to LPs including: geographical scope, investment procedures, structure of investors and key men provisions.

Marketing

Marketing of the fund to prospective investors is usually done through a marketing document (for example a private placement memorandum or "PPM"). This document will contain important regulatory restrictions on whom it can be marketed to (which vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction). The PPM will contain the key information about the fund such as the fund's organisation, investment strategy, the principal terms and conditions of the offering of a fund interest and any risk factors that investors should bear in mind when making their investment decisions.

Constitutional Document

The form of this document will vary depending upon the vehicle used, however as most funds take the form of a limited partnership, this is most often a limited partnership agreement (or "LPA"). The LPA is the core constitutional document for any limited partnership, and sets out the legally binding relations between the LPs and obligations of the GP. This should therefore include all aspects of the fund's lifetime from formation through operation and to termination. It should also outline the key commercial issues such as investment policy, profit sharing and fees and expenses as well as relevant constitutional and administrative provisions such as the circumstances in which the GP can be removed, reporting and accounting obligations and the provision of information by the GP to the LPs.

Closing

Once all the terms of the LPA have been settled, investors will sign up to the LPA and agree to be bound by its terms. It is common that investors will join a fund over a period of time (on a number of separate "closings") so the LPA will make provision for the possibility of investors coming into the fund after it has already started to make investments. As an example, certain types of American investors will be unable to sign up to the LPA until the fund is in a position to make its first investment and provision will be need to be made for this in the LPA. At the closing stages subscription documents are required to be executed by the investors, whereby the investors will have to give certain representations and warranties, to the fund, relating to their suitability to enter into the fund, and their compliance with the appropriate regulatory regime.

During these three phases the following are often regarded as the "key" legal issues:

Regulation

The manager of a fund will need to be authorised in the jurisdiction in which it carries out the management activities. If these management activities are carried out in the UK, the relevant regulator is currently the UK Financial Services Authority (although the newly elected government has stated it's intention to incorporate these regulatory functions into the Bank of England over the coming years). Fund managers may also operate from offshore jurisdictions, such as Jersey, Guernsey or the Cayman Islands. Reasons for doing so may include more favourable tax treatment on management fees or the desire to operate under a simpler regulatory system. However, there are reasons why it may be preferable to establish a manager onshore, given the potential changes the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFM) may bring when it reaches a final form. If the manager needs to be authorised in the UK (which it usually would be if the fund was managed from the UK), the manager would have to make an application to the UK Financial Services Authority (although this is likely to change in the future as highlighted above). Authorisation must be obtained before the fund may have its first closing but would not normally be required for the earlier stages. Approval normally takes 3 to 4 months to obtain, but may take longer if members of the management team need to undertake any additional training/exams or the manager has to recruit additional personnel in order to obtain authorisation. If the manager is to be authorised outside of the UK (e.g. if it is managed in an offshore jurisdiction such as Jersey, Guernsey or the Cayman Islands), the authorisation process may be quicker due to lighter touch regulatory regimes.

As set out above, the regulatory environment relating to private equity fund formation is due to change in both the U.S. and the E.U.. While it is difficult to fully quantify the impact of new regulations before they are fully approved and implemented, one can be certain the private equity will be subject to greater scrutiny than was previously the case.

Regulation in Kazakhstan

The regulatory environment in Kazakhstan is in an early stage of development with respect to the PE industry. According to FMSA Resolution no. 296 dated 25 December 2006, which has recently come into force in Kazakhstan, it is necessary for banks to allocate 100% provisions against loans issued to borrowers controlled by entities established in certain specified jurisdictions. As most PE funds are incorporated in these listed jurisdictions, this creates a major barrier to PE investment into Kazakhstan, as it does not allow these PE funds to restructure debts of their Kazakh portfolio companies. It is hoped that the Kazakh regulator will take in to the account capacity of private equity industry to assist and invest into Kazakh businesses, and reconsider its approach in this area.

Kazakh legislation on investment funds is at an early stage of development and has yet to fully align with the financial market's capacity to invest into the Kazakh economy. Sub-Clause 1 Article 4 of the Law On Investment Funds envisages two types of investment funds that require a license for investment portfolio management:

- Incorporated Investment Funds (akzionerniy investizionny fond); and

- Mutual Investment Funds (payeviy investizionniy fond) which can be created as open, interim and closed depending on how quickly clients are able to withdraw for such a fund.

A 'Mutual Investment Fund' operates with units provided by its holders under a trust management arrangement. Mutual investment funds are not legal entities, however, their investment size is usually much smaller than that needed for private equity investments. An 'Incorporated Investment Fund' (“investment fund”) is a joint stock company which exclusively accumulates and invests capital contributed by its shareholders and any returns generated from investments. Investment funds that do not attract third party funds but manage their own assets need a license for portfolio management. Such funds have to comply with specific limitations which are established for management companies of investment funds by the Investment Funds Law and by a special resolution of Kazakhstan’s central bank.

Investment funds are subject to six major restrictions in Kazakh legislation. These restrictions include those prohibiting funds from: (i) establishing subsidiaries; (ii) issuing financial instruments other than common shares; (iii) engaging in other types of activities other than investment management; and (iv) holding any assets outside of a specified type. Management companies are subject to an additional thirteen restrictions which include prohibitions on; (i) deals which fall outside the agreed investment scope of the fund; (ii) entering into transactions where there is a conflict of interests; (iii) loaning of the fund’s assets; and (iv) entering into derivative transactions (except where this is done for hedging purposes).

It should be noted that the Kazakh legislation regulates funds that have investment and accumulation of capital as their exclusive activities. As in practice most commercial entities invest and accumulate capital in one way or the other, the legislation is therefore very wide reaching. If the entity's constitutional documents provide that other types of activity may be performed, then the legislation will generally not apply, and the entity will not need to be licensed.

Sub-Clause 6 Article 69 of the Kazakh Law on Securities Market states that investment portfolio management is an activity performed in the interests of a client. This does seem logical as the regulation should cover professional service providers on securities market. However this is currently in contradiction with Sub-Clause 7 Article 4 of the Law On Investment Funds that requires incorporated investment funds to receive an investment portfolio management license if they invest without management companies. Perhaps the answer to such contradiction lies in the exclusivity of investment activities but it would be beneficial if the Kazakh legislature or regulator could acknowledge other types of investment funds, keeping in mind when doing so a proper balance must be maintained as to what should and should not be licensed. That is not a straightforward issue as can be seen in the current regulatory changes currently proposed in both Europe and the U.S.. Keeping the regulatory control at an appropriate but not overly burdensome level may quickly pay off for the country’s business sectors. It is very important to create an attractive economic climate and stimulate both domestic and international investors to establish funds in Kazakhstan rather than in other jurisdictions. The regulator now faces the challenge of implementing a reasonable regulatory regime through which capital may easily flow into the country’s emerging economy.

Governance Challenge

In addition to the expected increase in regulatory burden as outlined above, it is expected that there will be a greater focus on fund governance issues in the future. Indeed this trend has already been witnessed, with investors calling for increased transparency and information from fund managers alongside clearer policies on avoiding, and dealing with, conflicts of interest. These discussions have been supplemented by a number of principles and guidelines such as those mentioned above.

The Walker guidelines (published in November 2007) are a good example of how governance has become a more pressing issue recently in the UK in particular, recommending enhanced disclosure both by certain portfolio companies in the UK and by PE firms themselves. These guidelines, and others produced in different jurisdictions globally, tend to require more information to be disclosed publically. This higher disclosure burden may require portfolio companies to ensure that specified information is contained in their annual report and accounts, such as the identity of the PE funds that own the company and the senior executives of the fund who have oversight of the company, details of board composition and a business review containing information equivalent to that issued by a quoted company. Compliance with many of these guidelines is currently voluntary, and they tend to operate on a "comply or explain" basis.

Transparency and disclosure by a fund to its LPs, as opposed to the wider market, is a separate issue. While LPs are likely to have certain statutory information rights (for example, sections 28 and 24(9) of the 1890 Act), the LPA will invariably specify more extensive, bespoke rights. Larger, more sophisticated LPs (with the time and resources to make use of the further information), or those that require specific information for tax, legal or regulatory reasons, often demand, and receive, access to a greater amount of information, which can lead to what IOSCO has recognised as a "disclosure disparity" between larger and smaller LPs.

To the extent that a fund needs to comply with the Walker guidelines, a GP will also need to follow established guidelines such as the International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines when valuing assets and reporting to LPs.

Not surprisingly, the ILPA principles recommend greater transparency in relation to, for example, fee models to be provided to assist transparency of fee and carried interest calculations, ongoing disclosure of fees generated by the GP, disclosure of the GP's economic arrangements and organisational structure, and an LP entitlement to receive, on request, more detailed information on fund capitalisation, profit-sharing splits among principals, the breakdown of the individual commitments making up the GP commitment and other incentives

Conclusion

In summary, the private equity industry has faced a challenging time following the global financial crisis, and as a result will now have to adapt to meet the new legal and regulatory restrictions placed upon it in many different jurisdictions. Notwithstanding this, private equity has shown itself to be a valuable investment class, providing much needed capital and expertise into businesses which need them. These qualities are now as valuable as ever given the recent liquidity problems experienced by the traditional sources of capital in the banking sector. The returns from private equity have consistently exceeded traditional forms of investment and have proved to be highly profitable. The industry and its capital, should be encouraged and welcomed into emerging market economies, as both provide ample opportunities for businesses that seek to grow, and investors looking for returns.